Dead Man Walking

WNO's production of Jake Heggie's Dead Man Walking focuses on the opera's dramatic strengths.

Jake Heggie's opera Dead Man Walking doesn't have any tunes you'll be humming on your way home after seeing it, like Carmen's "Habanera" or Rigoletto's "La donna è mobile." Its score doesn't have any of those unforgettable earworms that slither through the popular works of Puccini, Verdi, and Wagner. Compared to other American operas, such as Philip Glass' Einstein on the Beach or John Adams' Nixon in China, it doesn't feel groundbreaking or even especially inventive. So why has it become the world's most popular American opera, being produced more than fifty times around the world since since its debut at San Francisco Opera during late 2000?

There are a few possible answers, including built-in audience awareness from the successful movie based on the same material (Sister Helen Prejean's 1993 non-fiction account of her time spent as a spiritual advisor to death row inmates), and perhaps the truth of the maxim "success begets success"; Dead Man Walking is a rarity -- a contemporary opera that premiered in a major house to great reviews and a receptive audience.

However, I would suggest a different reason: Dead Man Walking's success lies in its quintessential American character and its contemporary relevance. It's an unflinching portrayal of American culture and values set in harsh but gripping terms. Not enough has changed since Prejean's book was released in 1993 to make the story feel dated -- it could've have happened yesterday and might happen tomorrow. That makes it something unique: a contemporary that actually feels contemporary, giving audiences something they rarely if ever get to experience in an opera. Among similarly scaled operas, perhaps only Tobias Picker's An American Tragedy, an adaptation of Theodore Dreiser's 1925 novel about and social striving and stratification, has such a distinctly American sense of morality at its core.

From its Horatio Alger origins (Heggie was working in the SF Opera public relations department and had never written an opera when General Director Lotfi Mansouri gave him the opportunity of a lifetime), to the uniquely American paradox driving its central conflicts (a culture prone to violence responds with capital punishment), its musical quotes of Elvis, the appropriately blunt coarseness of its libretto, and overall lack of subtlety, Dead Man Walking is an operatic portrait of a deeply flawed country mired in an unending cycle of violence, inadequately rendered justice, and ultimately futile attempts at redemption.

A frequent knock of Dead Man is that its drama pulls us in more than its music, which is a view I've heard from a few critics and not a few audience members over the years, leaving them with the vague feeling that Dead Man isn't so much an opera as a dramatic theater piece with an ambitious, live soundtrack (the latter nevertheless usually find themselves deeply moved by the opera). Yet after seeing Dead Man Walking twice in the past two years (Opera Parallèle's 2015 production in San Francisco and now Washington National Opera's new production at the Kennedy Center last weekend) I'm convinced Heggie's score is the opera's quiet strength.

There are two recordings available to listen to beforehand (one is available on Spotify), but for people coming to the opera blind the easiest way in is to follow the motifs of the two leads: five notes (three rising followed by two descending) for the convicted killer Joseph De Rocher, and the melody of Heggie's original hymn "He Will Gather Us Around" for his spiritual advisor Sister Helen. Both appear in the prelude, which begins with and is dominated by the De Rocher motif, while "He Will Gather Us Around" is heard in full in the second scene. Heggie uses these motifs with increasing skill and effect as the story progresses, especially in the conversations between the nun and the condemned killer. Also note the two sharp blasts led by brass and percussion during the murder scene that return at judiciously chosen moments throughout the opera.

At one point Sister Helen asks De Rocher, "Are you frightened?" His response finds the violins and violas abruptly dropping the motif, leaving it to the basses and cellos, which underline his answer with ominous dread, followed by Sister Helen's music rising in reply. Sometimes the seven-syllable melody of the hymn sounds compacted into five notes, creating an opposing or paradoxical response to De Rocher's motif. When [spoiler alert] De Rocher finally admits his guilt to Sister Helen the motif accompanying the scene goes silent, and no music accompanies the confession, but it's followed by the entrance of expanded version of the motif, heard for the first time.

In his first opera Heggie doesn't wield these compositional tools with the practiced precision or sophistication found in Wagner or late Puccini, nor does his music possess its own sense of stand-alone splendor -- few contemporary operas do, and those composers who reach for it come usually take critical heat for the attempt (see the critical response to Marco Tutino's Two Women or Mark Adamo's The Gospel of Mary Magdalene). But that doesn't make Heggie's music less effective in its goal, only less obvious. The intelligence of his score can be obscured by the drama unfolding on stage, but it's there, creating a constant undercurrent of conflict pushing the story forward with increasingly effective results. That's no small feat, and the result is an opera with an emotional relentlessness that's as steady as a freight train. Dead Man Walking sits well musically within the form to please fans of the standard rep, and its relevance and dramatic urgency should appeal to new audiences.

Washington National Opera's first production of Dead Man Walking does an excellent job of balancing Heggie's music and Terrence McNally's blunt libretto to create a potent experience. In what's becoming a signature role, baritone Michael Mayes brings physical verisimilitude to his performance as De Rocher, along with a strong and convincingly powerful voice. He exudes a combination of fear and rage, impotence and cunning, and a keen awareness of his plight -- he wants to confess and yet it's a step he can't bring himself to take. Mayes looks and sounds like a killer, at least the kind we see in films and on tv, but McNally's libretto eventually reveals a more nuanced, conflicted psyche (don't quibble over the facile methods used to get there -- this isn't Wagner or Lulu), that almost renders him sympathetic. Almost.

Arriving at the prison by De Rocher's invitation, mezzo-soprano Kate Lindsey's Sister Helen is both De Rocher's antagonist and redeemer. Unfortunately Lindsey can't counter Mayes' feral portrayal with an equal amount of vocal power and physical presence, which creates a visual and aural imbalance on the stage. There's a nagging sense that Lindsey's nun just isn't strong enough to turn De Rocher toward redemption. It's not just the vocal difference -- Lindsey's voice is clear but it's not well-suited to such a large hall, or perhaps an opera with such a large orchestra. As Sister Helen her interactions with Mayes' De Rocher come off as delicate, even naive. Sure, she has conviction, but it doesn't seem strong enough to counter De Rocher's manifest evil.

The imbalance is exacerbated by Susan Graham's portrayal of De Rocher's mother. Graham's voice can fill any opera house and she's an exceptional actor. Even here, rendered nearly unrecognizable in cheap, dowdy clothes and an unflattering wig she's a formidable stage presence. Then there's an extra meta aspect to this particular production which finds Graham returning to the opera for the first time since originating the role of Sister Helen in the San Francisco premiere sixteen years ago. Caught between Graham's powerful, completely convincing portrayal of the distraught mother and Mayes' cunning killer, Lindsey's Sister Helen isn't big enough to hold the center, nor nuanced enough to be a contrasting focal point between these opposing dramatic poles and powerhouse voices.

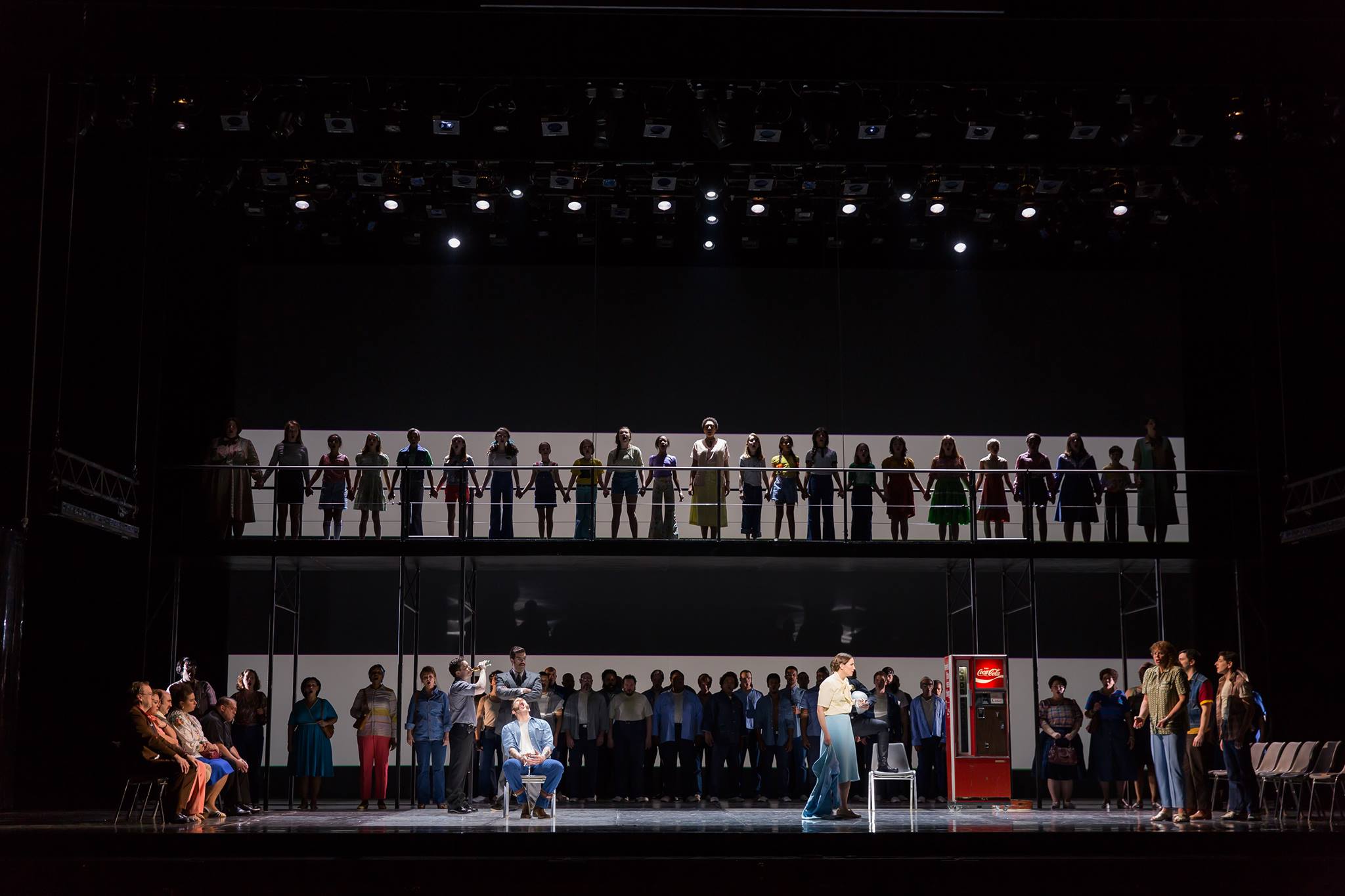

Allen Moyer's set design and Greg Emetaz's lighting create a stark yet versatile staging enabling the story to flow well. Their work, combined with Francesca Zambello's straightforward direction and Michael Christie's taut conducting (in his company debut), gives this production a driving momentum that's nearly Aristotelian in its sense of focus. The opening is brutally staged, and even if the audience can't see the worst of the violence it's palpably created through the music and direction. There are sections where Zambello has cast members take a seat on either side of the stage when they're not singing, which I initially found confusing, and only figured out what they were doing as the execution scene came into view. Apart from that, the opera moves with cinematic clarity and rhythm.

The strong supporting cast includes Jacqueline Echols as Sister Rose, Timothy Bruno as a nasty warden, Clay Hilley as a priest whose sense of redemption is a far cry from Sister Helen's, Matthew Hill and Simon Diesenhaus as De Rocher's brothers, and Wayne Tiggs, Kerriann Otano, Robert Baker, and Daryl Freedman as the parents of De Rocher's victims.

Dead Man Walking runs through March 11 at the Kennedy Center Opera House. Get tickets here.

If you liked this, like A Beast in a Jungle on Facebook for more.

All photos by Scott Suchman.