In the Groove

Herman Leonard was so broke during the 1940s that he couldn't afford the cover charge at New York's jazz clubs, so he bartered his way inside by offering to take photographs of the musicians. The results launched a career that produced dozens of iconic photographs of American jazz artists, capturing not the only musicians at work, but the unfolding of a distinct era in American music history. Leonard's talents with a camera quickly became evident to the musicians and the people running the clubs, so they gave the photographer free rein to get in close. Leonard's images fill in the lines of their subject's biographies, leaving the viewer with what feels like a face-to-face encounter, or perhaps the pleasure of having the best seat in the house with an invitation to go backstage after the gig. At its best, Leonard's photography manages to convey the essence of one artistic expression through the use of another, expanding the realm of both in the process.

His work graces the covers of numerous classic and influential jazz albums, and many of his photographs have become the definitive image their subject in the public's eye. Twenty-eight of his photographs are now on display in an exhibit titled In the Groove: Jazz Portraits by Herman Leonard at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery, expertly chosen by Ann Shumard, the museum's senior photography curator, and on view until February 20, 2017. It's essential viewing for anyone interested in the medium and the history of jazz.

Taken between the years 1948 - 1960, the photographs document jazz's post-war transition from the easy accessibility and pleasures of the big bands toward be-bop, small ensembles, improvisation, and the experimentation which has come to represent and define the genre's most revered artists.

They're portraits of both musicians and an era, defining each in rich black and white, selenium-toned gelatin silver prints. Leonard served a one-year apprenticeship under Yousuf Karsh, who taught the young Pennsylvanian how to use lighting and off-camera flashes. Leonard's application of those techniques, along with the omnipresent cigarette smoke swirling around his subjects, are stylistic signatures, like the brushstrokes on an impressionist painting. Yet labeling these photographs as portraits is partially misleading -- the images capture their subjects at work, and in that sense Leonard is a photojournalist as much as he is a portrait artist, and it's the photojournalistic quality of seeing the artists at work that powers the allure of the portraits.

That alone makes In the Groove compelling, but there's more. Shumard's choices reveal additional contextual narratives regarding the subjects and the era, especially for viewers familiar with the biographies of those pictured beyond the details listed on the informational cards next to each portrait (which don't shy away from acknowledging the presence and effects of drugs and alcohol on those pictured).

Take the portraits of Art Blakey and Buddy Rich: Blakey, the foster son of Seventh Day Adventists who grew up in a tough environment in Pittsburgh, began his musical career as a child playing the piano in church before switching to the drums at the point of a gun. Blakey converted to Islam and spent a couple of years in Africa before creating the seminal Jazz Messengers band. In the Portrait Gallery's exhibit Leonard's portrait of Blakey looks like the embodiment of "Moanin'" the title of one of his most famous compositions. In the image the viewer senses they've caught the drummer in the middle of more than just a downbeat, leaving them to wonder about the source of his facial expression and physical posture.

Rich grew up in performing vaudeville houses, born in Brooklyn to Jewish parents, and was a bandleader as a child. As an adult he was almost as famous for his volatile temper as he was for his formidable skills on a drum kit, and he was a frequent presence on television during the 1950s. His portrait shows a man with wide-open grin beating a snare drum with the glee of an adolescent discovering a stockpile of illicit contraband. Peers born two years apart into different worlds, the juxtaposition of their portraits raise questions on how race and culture shaped their careers.

Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald, the First Ladies of American music, are present, each revealing aspects of their unique careers and personalities. In the 1949 photo of Vaughan, whose nickname was "Sassy," the singer appears poised, open, vibrant, and engaged. She could be singing or she could be telling a joke, but she's definitely in control of her surroundings, which remained the case until she started mixing her career and personal life together a decade later. Holiday's photo, taken 1949, shows the singer slightly puffy, tentative, with a faint trace of apprehension in her face and body language. Holiday's troubles would grow worse in the coming decade, and Leonard's image reads as if Holiday has spotted Cassandra seated in the audience. Then there's Ella, joyfully owning a room full admirers, every trace of shyness vanquished in front of an audience.

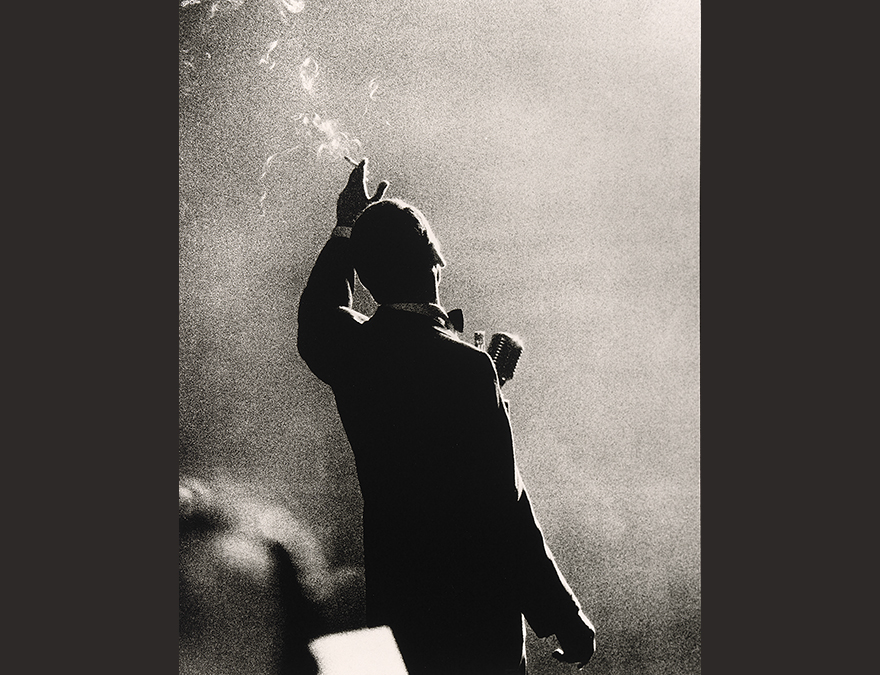

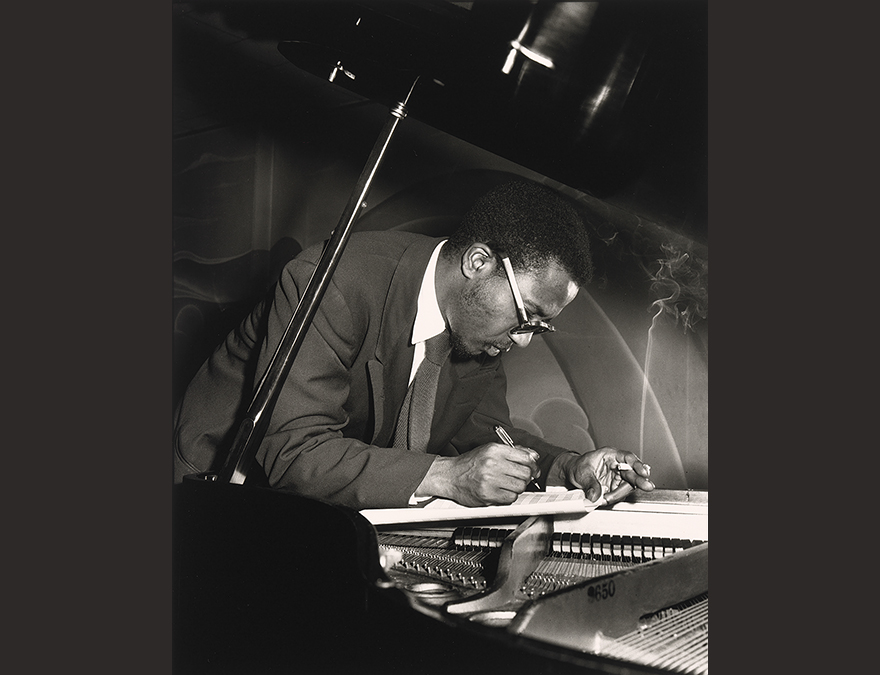

Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra, two titans of their respective realms, are captured in silhouette. Ellington is seated at a piano, a beam of light illuminates the man while his head casts a shadow onto the instrument before him. Ellington holds his hand aloft, and it's unclear whether he's thinking out a shift, pausing dramatically, or willing something into existence by the sheer power of his genius. Sinatra's arm is also aloft, holding a cigarette, but without even seeing his face the viewer knows Sinatra might as well be the world on a string.

Those unfamiliar with Louis Armstrong's history, or who haven't seen Satchmo at the Waldorf, Terry Teachout's one-man play examining the darker side of Armstrong's popularity with white audiences and the problems it gave him with fellow musicians like Miles Davis, might be taken slightly aback by Leonard's picture of the singer/trumpet player. The photograph is a study of ennui and exhaustion, a portrait of boredom and weariness. Contrast the image of Armstrong with the photo of Thelonious Monk bent over a piano, pencil in hand and cigarette in the other, putting down the future of jazz on a piece of paper, beholden to nothing but his own genius. Both are at work, one whose future lies ahead, the other well aware it's passed.

Perhaps the most striking photo is that of Chet Baker taken in 1956, especially when compared to the image of Armstrong and the one of Quincy Jones shot in 1955. Like Armstrong, Baker and Jones were trumpet players. Baker, only a couple of years older than Jones, was also a gifted vocalist. In Baker's portrait his face is obscured by his hands holding his instrument to his forehead. Wearing a white t-shirt and captured in profile with his head facing down and shoulders hunched as if to deflect a blow, the image of Baker is that of a man defeated (the following year he began using heroin, which would adversely impact his career for the remainder of his life). Armstrong's image suggests a resigned state of surrender. Baker is under siege, and the image stands out among the others because it feels like an act of voyeurism. Armstrong's portrait isn't flattering, but not for a moment does it feel like it could have been taken without its subject's awareness.

Jones, also shot in profile, stands erect, his head set straight ahead, exuding poise and confidence. His arms extend before him, bent at the elbows, and his fingers extend outward from hands held flat, as if he might be directing something detailed and precise. In his mouth is a toothpick, in his hands he holds a pencil as if it's a navigational instrument. With its lack of shadows and cigarette smoke, it's a portrait unlike the others in the simplistic clarity of its composition and subject.

Of all the musicians represented on the walls of In the Groove, Jones' career could be viewed in some ways as the most successful, especially in terms that don't take musical influence or artistic legacies into account. Baker's could well be the opposite (notwithstanding the presence of Charlie Parker and Holiday) -- a tremendous talent sidelined by addiction who never reached his full potential.

While I think the portraits of Baker and Jones are the most revelatory displayed in the exhibit, Leonard took more photos of both men which in some ways bear a greater aesthetic resemblance to the rest of what's presented here. Why Shumard chose these specific images creates an interesting question. If asked, my answer would be they allow viewers to see them as doors set opposite one another leading into and away from a shared central story. Through one door is Baker, a talent now barely known to anyone except jazz enthusiasts, one of countless talented artists laid low by addiction and inner demons. Through the other is Jones, whose success in the realm of pop music renders his roots in jazz an almost obscure footnote in his biography.

Between these two doors hang the rest of Leonard's portraits, lining the walls of our shared experience, evidence of a vanished era, an essential moment in American musical history, and acknowledging the inestimable cultural and artistic contributions of black Americans, keeping the the beat forever in the groove.

All photos courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / © Herman Leonard Photography, LLC.

If you liked this, why not like A Beast in a Jungle on Facebook for more?

All photographs